About Executive Order 9066

|

|

| Summons to report for mass removal and incarceration, 1942. Gift of Anonymous (95.243.1) |

|

|

|

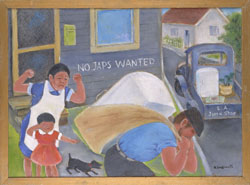

| Anti-Japanese sign in Livingston, California, ca. 1920-1930. Gift of the Yamamoto Family (98.54.22) |

|

|

|

| Henry Sugimoto, Attacked Pearl Harber (Attacked Pearl Harbor Hawaii), ca. 1947. Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.74) |

|

|

|

| Henry Sugimoto, Documentary, junkshop man took away our icebox, ca. 1942. Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa (92.97.89) |

|

The Presidential decree known as Executive Order 9066 authorized the largest forced relocation of people in U.S. history.

This site presents an archived version of the stories collected through the Remembrance Project—a three-year online initiative launched by the Japanese American National Museum in 2012 in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the signing of E.O. 9066—featuring the portraits and stories of those whose lives were affected by World War II and E.O. 9066. On the Remembrance Project site, visitors can learn about the unique experiences through viewing the Tribute stories as well as general background information on the specific camps.

Seventy years ago, the power to forcibly remove anyone from any part of the U.S. and to detain them indefinitely was granted to the military by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Executive Order 9066 was issued on February 19, 1942, in the name of national security. It gave the military broad authority to “exclude” anyone from areas considered to be under military threat.

As a result of Executive Order 9066, the U.S. government forced more than 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast and parts of Hawai‘i and incarcerated them in prison camps where they were held without charge or trial. Two thirds of the 120,000 were American citizens. It was the largest forced relocation in U.S. history.

In the wake of Japan’s attack at Pearl Harbor, wartime fears, outrage, and hatred took aim at people of Japanese descent living in the U.S. The sweeping destruction of the U.S. naval fleet led to the belief that Japanese Americans must have aided in the attack. Long-standing hostilities toward Japanese immigrants were inflamed. Fears that Japan would launch a full-scale invasion of the U.S. West Coast mounted, and rumors of spying and sabotage were rampant. Newspapers of the time conveyed the sense that the U.S. was at war with a race as much as it was at war with a nation.

Japanese and Japanese Americans were unquestionably the target of Executive Order 9066, but this was not actually stated in the language of the ruling. In fact, Executive Order 9066 gave military commanders the power to remove anyone they chose, American citizen or not, from any part of the U.S.

The dreaded Japanese invasion of the U.S. West Coast, of course, never occurred, and stories of Japanese Americans helping the enemy turned out to be baseless. None of the 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans removed from the West Coast and Hawai‘i were ever convicted of spying or sabotage.

Today, the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II is widely recognized as a grave injustice against an innocent group of people. In 1982, the Federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded that the Japanese American internment was the result, not of military necessity, but of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In 1988, President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government. More than $1.6 billion in reparations have been paid to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated.

Since its inception in 1985, the Japanese American National Museum has chronicled more than 130 years of Japanese American history—from the first Issei generation through the World War II incarceration to the present day. Each year, hundreds of thousands visit JANM both onsite and online. Through its Manabi & Sumi Hirasaki National Resource Center, visitors can access selected highlights from the museum’s permanent collection of over 80,000 unique artifacts, documents, and photographs can be viewed at janm.org/collections.

The Japanese American National Museum is proud to contribute through this Project and its other ongoing work to the growing number of resources documenting the forced removal and incarceration and to honor the many varied experiences of those who lived through it.