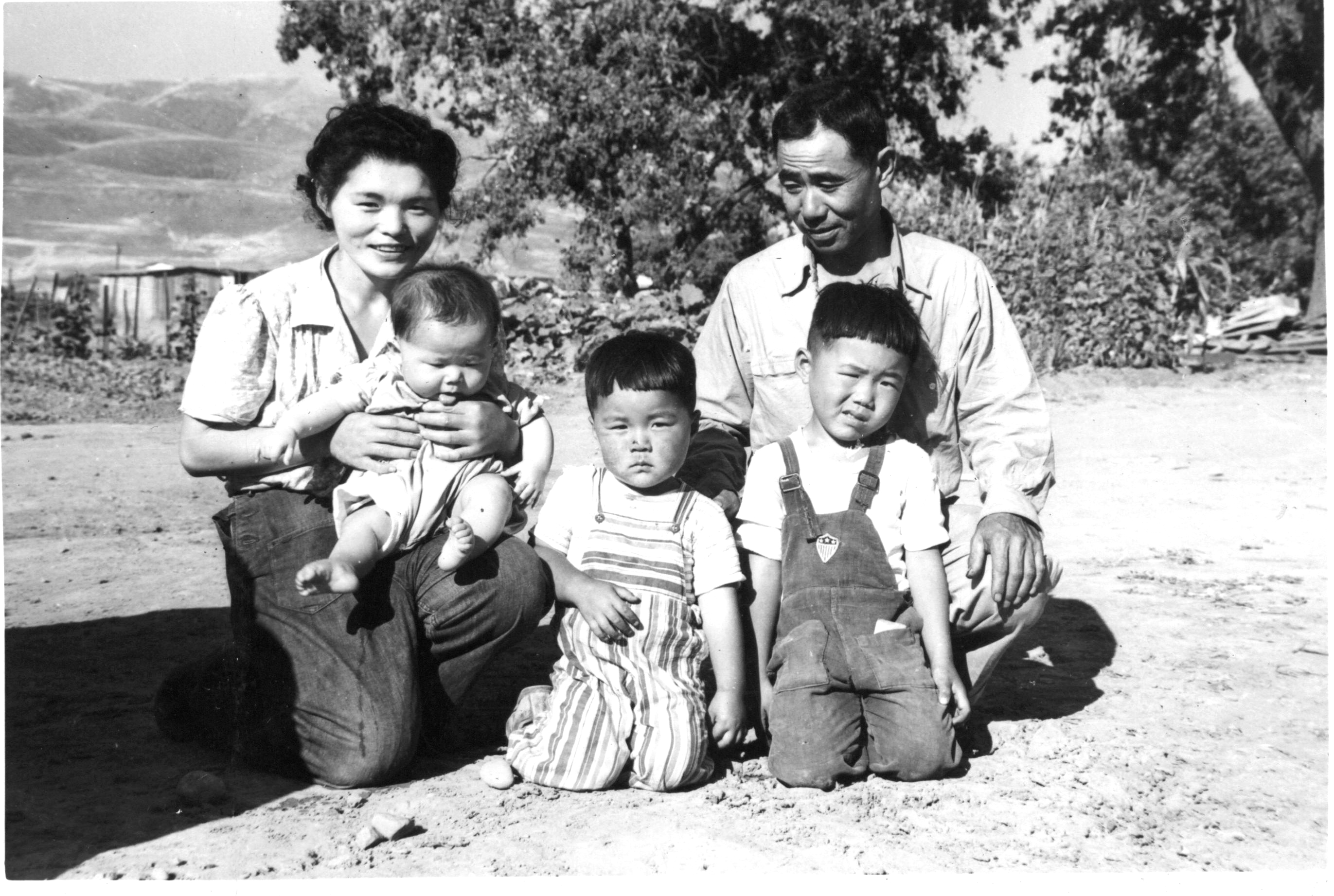

Hayato & Rie Sakamoto & Family

Camp Name:

Tule Lake

Block Number:

100

Barracks Number:

4A

Hayato & Rie

Sakamoto

As a docent at the Japanese American National Museum, I have the privilege of telling visitors about the Japanese American immigrant experience. The story I tell is very personal because I share the lives of my parents, Hayato & Rie Sakamoto.

Both of my parents were raised in Japan. My father was born in Japan and came to America as a nineteen year old in 1924. My mother was born in California, but sent to Japan as a small child and did not return until she was a young adult. My father was the youngest of eight children with little hope of sharing in the legacy of a small family farm. My mother’s family was very poor: that is why she was sent to Japan to be raised by her grandparents When the war with Japan started, my parents were rounded up at gunpoint like all Japanese Americans on the coast and imprisoned at the Tulare County Fairgrounds and later at the Gila River concentration camp. My father’s faith in America was shaken to the core. He said that there was no future here for us and he intended to return to Japan after the war. Once his intention was revealed to WRA authorities, our whole family was sent to the Tule Lake concentration camp in California.

Tule Lake was re-designated as a “segregation center” by the War Relocation Authority for those who were considered of suspect loyalty because they did not answer “Yes-Yes” to two confusing and insulting “loyalty” questions or requested repatriation. My father said that within a month of their arrival at Tule Lake, the Army took over the camp and brought in huge numbers of soldiers with tanks patrolling the grounds at night. He became concerned for the family’s safety because of rumors that the Army intended to start killing people. Fortunately, the rumors did not come to pass, but the conditions at Tule Lake remained the worst of the WRA prison camps until its closing on March 28, 1946.

After almost four years in three prison camps, my parents planned to return to Japan, but decided to remain in America after receiving news of the post-war devastation in Japan. Luckily, my father was a skilled farmer and was able to find work after leaving the prison camp in 1946. He later decided to strike out on his own as a sharecropper. Our family eventually moved into a farm shack in the middle of a cherry orchard in San Jose for the next twelve years while growing strawberries. My parents worked very hard to make ends meet, improve their economic situation, and raise four children in the years after the war.

In later years, I asked my father when America started to feel like home and not Japan. He said that by the early 1950s things had improved for Japanese Americans. When he became eligible for citizenship, my father said he realized America was really his home and became a citizen in 1954, after 30 years in this country, four of which were spent in prison. He spent the last 30 years of his life as a U. S. citizen and saw his children achieve the dreams he and my mother had for us.

In 1982, a year before his death, I interviewed my father to capture his thoughts about his life in America. I asked him whether he was bitter about the way the U. S. government treated the Japanese in this country before, during, and after the war. He said he held no bitterness because there wasn’t time to dwell on such things because he had to put food on the table. Looking back on my parents’ lives, I am forever grateful for the many sacrifices they made for us so that we could achieve the American dream. I am also grateful that I can share their experiences and remember them each week as I tell their truly American stories to museum visitors.